Surround Sound

American anthropologist Steven Feld spent 25 years of his career in the rainforests of Papua New Guinea exploring how the music of the Bosavi people is closely tied to their sensorial world. So is ours, by the way.

How did your early years as an anthropologist in Papua New Guinea mark your career?

Steven Feld: I learned that rainforests are extraordinary places to study adaptation: obviously you develop acoustic acuity. Sometimes I was in the forest with my parabolic microphone, trying in vain to find the sound of a bird in the trees, and these 11-year-old-kids would laugh at me, grab my hand, and point my microphone exactly in the right place. How did those kids know that I was mistaking the height of the sound for the depth of the sound? Their knowledge had been shaped by a tremendous amount of practical experience. As a foreigner, this is how I learned to hear rainforest sound as space.

You were studying the ways that bird sounds influence the songs of the Bosavi people, who believe that their ancestors are heard in the voices of birds. Does that spirituality play a role in their music?

Feld: Yes. There’s a visceral way the lives of the Bosavi people are tied to the lives of rainforest birds. To use the word ‘spirit’ or ‘nature’ is almost banal in this kind of setting. For them, birds are about social relations, transformations through life and death. Every bird is heard as a living presence and a spiritual absence. I was astonished to discover that the best composers were also the best ornithologists. Why would one have to know 125 species of birds, their sounds and their seasonal cycles, just to be a good composer? Obviously, to write these songs they have to intimately know the sound world of these birds because they are the human past living in the present. To map this world they have to know how birds sound and travel. This is an example of how ecological knowledge and cosmological knowledge are deeply connected for the Bosavi people.

In the West do we have a more structural or “abstract” approach?

Feld: I don’t like to make generalizations about the West and non-West. For me anthropology is a technique for making the more intuitive and sensuous world of indigenous art more legible, helping people get a bit closer to realities that previously seemed more “exotic” or “strange”. That’s an artistic and intellectual commitment. It’s also a political commitment, an ethical concern to reduce the tendency to fabricate narratives about the “primitive”, and the way these fabrications court racist or negative stereotypes. I’m interested in making clear that there are other poetic systems like the one I studied in Bosavi that are as rich as the poetic systems in European cultures. And even if the Bosavi musical system may seem “impoverished” to Westerners compared to orchestral music, it in fact involves forms of musical imagination as complex as any we find anywhere in the world history of music.

Does your research then open us up to a different idea of what a song is?

Feld: I hope so. Instead of songs as the structural conjunction of music and language, I think of songs as the centerpiece of the study of ecology, a mixture of social biography and knowledge of place. A critical element in all this is emotion. Songs are not just about knowledge—they’re about knowledge that is saturated by sentiment, saturated by understandings of attachment and relation. Added to that, Bosavi songs are an archive of environmental consciousness. Every song is called “a path”, meaning a history of places and memories. If I wanted to remember today in song, for instance, I would create a “path” from my hotel to this café, and in sequence I would note things like the signs of streets and shops, the colours I saw, the changes of light and air, the flowers, the smells of breads and foods in the market, the sounds of trucks and bikes that passed by me. The making of song joins the making of memory and the making of place. The poetic material comes from the movement of people through space and involves the sensuous language of light, sound, and motion. These things collect like memories on our bodies. The American composer John Cage once asked a wonderful question: “Which is more musical? A truck passing by a music school or a truck passing by a factory?” That is a way of saying that all music is sound and all music is environmental. For the Bosavi people, just like for Cage, song is all about context, about transforming and remembering the world as it is heard and felt.

I’ve found out that bells mediate the history of spirituality and labour in European locations like birds mediate the understanding of time and the spiritual world in the New Guinea rainforest

Which brings us to your more recent explorations of the sounds of bells around the world. Are you trying to draw larger connections between human relationships with the sound environment?

Feld: In recent years I have wandered through villages and towns in six European countries listening to bells. I’ve noticed how people seemingly don’t pay attention to bells, but in fact are very aware of them. In short I’ve found out that bells mediate the history of spirituality and labour in European locations like birds mediate the understanding of time and the spiritual world in the New Guinea rainforest. Who owns time—the church or the state? Who has the right to ring the hours that tell us to go to church or to go to work? The reach of the sound of a church bell is like the reach of a radio station broadcast; the limits of audition define what can be called a “community”. The point is that humans coexist and are co-present in the world with many others: with animals like birds, with technologies like bells, with all sorts of animate and inanimate things. In that coexistence bells and birds produce consciousness of space and time through sound.

About Steven Feld

An American anthropologist of sound, Steven Feld is Professor Emeritus at the Department of Anthropology of the University of New Mexico. To better describe his work, Feld coined the word ‘acoustemology’, a combination of the words acoustics and epistemology. In November 2015, he was a keynote speaker at the annual ANUAC Congress (Associazione Nazionale Universitaria degli Antropologi Culturali) held at unibz. For more on Feld, see www.stevenfeld.net.

Related Articles

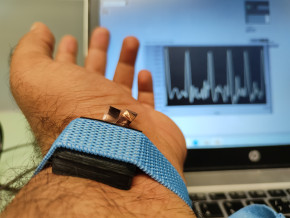

Tecno-prodotti. Creati nuovi sensori triboelettrici nel laboratorio di sensoristica al NOI Techpark

I wearable sono dispositivi ormai imprescindibili nel settore sanitario e sportivo: un mercato in crescita a livello globale che ha bisogno di fonti di energia alternative e sensori affidabili, economici e sostenibili. Il laboratorio Sensing Technologies Lab della Libera Università di Bolzano (unibz) al Parco Tecnologico NOI Techpark ha realizzato un prototipo di dispositivo indossabile autoalimentato che soddisfa tutti questi requisiti. Un progetto nato grazie alla collaborazione con il Center for Sensing Solutions di Eurac Research e l’Advanced Technology Institute dell’Università del Surrey.

unibz forscht an technologischen Lösungen zur Erhaltung des Permafrostes in den Dolomiten

Wie kann brüchig gewordener Boden in den Dolomiten gekühlt und damit gesichert werden? Am Samstag, den 9. September fand in Cortina d'Ampezzo an der Bergstation der Sesselbahn Pian Ra Valles Bus Tofana die Präsentation des Projekts „Rescue Permafrost " statt. Ein Projekt, das in Zusammenarbeit mit Fachleuten für nachhaltiges Design, darunter einem Forschungsteam für Umweltphysik der unibz, entwickelt wurde. Das gemeinsame Ziel: das gefährliche Auftauen des Permafrosts zu verhindern, ein Phänomen, das aufgrund des globalen Klimawandels immer öfter auftritt. Die Freie Universität Bozen hat nun im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts eine erste dynamische Analyse der Auswirkungen einer technologischen Lösung zur Kühlung der Bodentemperatur durchgeführt.

Gesunde Böden dank Partizipation der Bevölkerung: unibz koordiniert Citizen-Science-Projekt ECHO

Die Citizen-Science-Initiative „ECHO - Engaging Citizens in soil science: the road to Healthier Soils" zielt darauf ab, das Wissen und das Bewusstsein der EU-Bürger:innen für die Bodengesundheit über deren aktive Einbeziehung in das Projekt zu verbessern. Mit 16 Teilnehmern aus ganz Europa - 10 führenden Universitäten und Forschungszentren, 4 KMU und 2 Stiftungen - wird ECHO 16.500 Standorte in verschiedenen klimatischen und biogeografischen Regionen bewerten, um seine ehrgeizigen Ziele zu erreichen.

Erstversorgung: Drohnen machen den Unterschied

Die Ergebnisse einer Studie von Eurac Research und der Bergrettung Südtirol liegen vor.