The Myth Buster: Robin Warren

Ulcers are caused by stress and diet, right? If you think so, you’re actually in good company because most people will nod their heads in agreement with you. But the truth is almost 35 years ago a little spiral-shaped stomach bacteria known as Helicobacter pylori was fingered as the real culprit. Pathologist J. Robin Warren is one half of the Nobel-Prize-winning duo from Australia that turned the medical establishment on its ear in 1982, when they showed a link between Helicobacter and peptic ulcers. Warren is visiting EURAC in April to take part in the ‘Meetings with Nobel Laureates’ series. Academia caught up with him in his home in Perth, Western Australia to talk about what it takes to usurp a myth.

It was just another day in the lab on 11 June 1979 when you noticed something unusual in the stain of a gastric biopsy. For the next two years you would study it in depth before the physician Barry Marshall arrived on your doorstep. Tell us about that first moment you saw the telling “blue line”.

Robin Warren: It’s something I won’t forget. It was on my birthday. I was looking at a fairly standard gastric biopsy with a severe form of active gastritis. I noticed there was this funny-looking blue line on the surface of the stomach epithelium. So I took a closer look and I saw masses of bacteria growing there. I showed it to my colleagues, and they insisted they couldn’t see anything— just a little ‘muck’ on the surface.

Why couldn’t they see it if you could?

Warren: It was a well-known fact at the time that bacteria couldn’t grow in the stomach, and by and large, that’s right— stomach acid kills bacteria you swallow. It’s also true they were very hard to see. I was experimenting with silver stains at the time, so I thought, “I’ll try the silver stain on these organisms”—and, as it turned out, they stained beautifully. I showed these new stains to my colleagues, and they agreed that the bacteria were there. But since they weren’t supposed to be there, and they didn’t know what they were, they thought they were an anomaly. Nonetheless, they suggested that I go look for some more, and when I started looking for the bacteria, they weren’t really hard to find. In fact, they were in 30 to 40 per cent of gastric biopsies.

But how could these bacteria survive in the stomach?

Warren: While I was studying the pathology of these bacteria, I saw that they were growing right down on the surface of epithelium, and all those epithelium cells were secreting mucous. So the bacteria were growing very happily underneath this mucous in a neutral pH environment.

So with your pathology work on this strange bacteria nearing its completion in 1982, Doctor Marshall’s clinical input must have been quite a welcome addition.

Warren: We had no clinical information at all on the biopsies we were studying. So after Barry became interested in my research, he and others biopsied 100 consecutive outpatients who were sent in for epigastric pain. Barry wrote out a huge protocol of symptoms and the patients would tick off what they had. So we had extensive notes of anything the patients had clinically as well as biopsies for culture and for me to look at. We found that every patient with duodenal ulcers was infected with the bacteria, and most patients with gastric ulcers were infected with the bacteria. It didn’t seem too far out to suggest that the infection was causing the ulcers, and that’s what we wrote up.

You’re referring to the two initial letters you wrote to The Lancet medical journal in January 1983. They were rejected by the establishment. The Gastroenterological Society of Australia refused to admit you into their annual conference. Nobody believed you. What did you do then?

Warren: We presented our definitive paper at a Campylobacter conference in Brussels in 1983, and it was the hit of the conference. It caught the attention of Martin Skirrow, the chairman of the conference. The editor of The Lancet was very interested in publishing the definitive paper, but the trouble was they had to get it peer-reviewed, and there were no peers to review it.

How so?

Warren: It was a double paradigm shift. First of all we were saying that bacteria could grow in the stomach, and everyone knew bacteria could not grow in the stomach. And then we were saying that these bacteria (that everyone knew weren’t there) were in fact causing ulcers, and everybody knew that ulcers were caused by stress and too much alcohol, and so on. And the editors couldn’t find any scientist who would confirm these findings. But Skirrow repeated our work, got the same results as us, and they believed him.

“First of all we were saying that bacteria could grow in the stomach, and everyone knew bacteria could not grow in the stomach. And then we were saying that these bacteria were in fact causing ulcers and everybody knew that ulcers were caused by stress.”

But even with a published paper in a respected medical journal like The Lancet, you still had difficulty being accepted by the medical establishment.

Warren: The specialists thought we were wrong. Our paper was printed on the first two pages of New York Times’ science section that same year. That in turn was reproduced around the world. The patients read about this in the newspapers and they took it right to their general practitioners. We started getting letters from GPs asking us how to treat these patients. So we sent details to them and there was great success at treating these people. The specialists didn’t care though. In Australia, it was not until about 1990 at an official meeting of gastroenterology that it was decided Helicobacter was the official cause of duodenal ulcers and that correct treatment was to eradicate the bacteria. It was even longer in America because of the influence of the drug companies who funded university research. They didn’t want to lose sales on their anti-acid drugs.

Up to 50 per cent of the world’s population is infected with Helicobacter, and up to 85 per cent of those infected do not experience symptoms. Why is it asymptomatic in so many people?

Warren: It’s the same with many kinds of infections—they can kill you, cause a mild disease, or something in between. They don’t always have the same effect. In the case of Helicobacter, all cause gastritis, but most of them don’t cause symptoms. There are no pain receptors on the mucosa; you can get quite severe infection of the mucosa and you won’t know unless you get an ulcer.

Do you think there is any possibility that the bacteria could have an unknown positive role in the stomach’s microbiota?

Warren: Frankly, I don’t know what good they could do. I’ve never seen an infection that was not causing damage to the stomach. They’re actually stuck on the surface of the epithelium cells, and I can’t imagine the epithelium cells liking that. The worse case scenario is you have an epithelium that totally loses its structure. So I can’t see them being a good thing. I found out that I had it, and I got it treated right away. We suspect most patients were affected as babies. As far as we know, the inflammation stays with you all of your life, and it doesn’t go away until you die.

So why isn’t everyone being treated?

Warren: You can’t force people to be treated; it’s an individual decision. And we’re talking about millions of people, which is not realistic. As well, antibiotics do have side effects, and if you treat millions of people you will run into cases of complications.

Since your discovery, papers on Helicobacter have grown from about 200 per year to 1,500, and they are now finding potential links between the bacteria and many other human health issues. That must make you proud.

Warren: The whole thing has gone way beyond what Barry and I were doing at the time. Now every branch of medicine is doing something on it. I’ve retired now, but Barry, who is 14 years younger than me, is trying to produce a harmless form of Helicobacter as a delivery method for vaccines. These bacteria would be genetically modified with antigens in them from other diseases. So in addition to producing antibodies against the Helicobacter, the body would also create antibiotics against the other organisms. The Helicobacter would cause the gastritis for a year at the extreme harmless end of the infection range and then go away. If he succeeds, it will be a very nice way of giving vaccines. You’d just take a little drink of the stuff, and you could be inoculated against any number of different diseases. I think it’s a damn good idea.

Why did your scientific partnership with Doctor Marshall work so well?

Warren: I am a quiet person and I like to sit in the laboratory and look at the specimens. Barry Marshall is a much more outgoing person who likes to talk to people and spread the news. I quieted him down a bit, and he made a bit of noise for me—so between the two of us, we got it right.

Related Articles

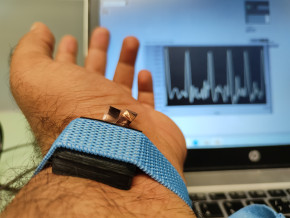

Tecno-prodotti. Creati nuovi sensori triboelettrici nel laboratorio di sensoristica al NOI Techpark

I wearable sono dispositivi ormai imprescindibili nel settore sanitario e sportivo: un mercato in crescita a livello globale che ha bisogno di fonti di energia alternative e sensori affidabili, economici e sostenibili. Il laboratorio Sensing Technologies Lab della Libera Università di Bolzano (unibz) al Parco Tecnologico NOI Techpark ha realizzato un prototipo di dispositivo indossabile autoalimentato che soddisfa tutti questi requisiti. Un progetto nato grazie alla collaborazione con il Center for Sensing Solutions di Eurac Research e l’Advanced Technology Institute dell’Università del Surrey.

unibz forscht an technologischen Lösungen zur Erhaltung des Permafrostes in den Dolomiten

Wie kann brüchig gewordener Boden in den Dolomiten gekühlt und damit gesichert werden? Am Samstag, den 9. September fand in Cortina d'Ampezzo an der Bergstation der Sesselbahn Pian Ra Valles Bus Tofana die Präsentation des Projekts „Rescue Permafrost " statt. Ein Projekt, das in Zusammenarbeit mit Fachleuten für nachhaltiges Design, darunter einem Forschungsteam für Umweltphysik der unibz, entwickelt wurde. Das gemeinsame Ziel: das gefährliche Auftauen des Permafrosts zu verhindern, ein Phänomen, das aufgrund des globalen Klimawandels immer öfter auftritt. Die Freie Universität Bozen hat nun im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts eine erste dynamische Analyse der Auswirkungen einer technologischen Lösung zur Kühlung der Bodentemperatur durchgeführt.

Gesunde Böden dank Partizipation der Bevölkerung: unibz koordiniert Citizen-Science-Projekt ECHO

Die Citizen-Science-Initiative „ECHO - Engaging Citizens in soil science: the road to Healthier Soils" zielt darauf ab, das Wissen und das Bewusstsein der EU-Bürger:innen für die Bodengesundheit über deren aktive Einbeziehung in das Projekt zu verbessern. Mit 16 Teilnehmern aus ganz Europa - 10 führenden Universitäten und Forschungszentren, 4 KMU und 2 Stiftungen - wird ECHO 16.500 Standorte in verschiedenen klimatischen und biogeografischen Regionen bewerten, um seine ehrgeizigen Ziele zu erreichen.

Erstversorgung: Drohnen machen den Unterschied

Die Ergebnisse einer Studie von Eurac Research und der Bergrettung Südtirol liegen vor.