Does she (Ever)Rest?

Chatting all things altitude related, Rachel Turner, altitude physiologist at the Institute of Mountain Emergency Medicine, tells us more about terraXcube – Eurac Research’s extraordinary new centre for extreme climate simulation.

I heard that you haven’t been getting much sleep recently – why is that?

Rachel Turner: Indeed, none of the team have! However, we are really enjoying this time. We have finally reached the point where we can launch human physiological/medical research in our new hypobaric, climate enabled lab, the terraXcube, and we have ambitiously started with three very large, collaborative projects running back to back. It is a much anticipated time for our growing team and an opportunity to really put the large cube through its paces. Currently, I am working on an exciting project called ‘Hypoxyplasma’, led by my research colleague Christoph Siebenmann – the project includes hosting groups of male volunteers for five days and four nights in the terraXcube either at a hypobaric hypoxic equivalent to 3500m or sea level. The groups have been excellent to work with, however the study hours are intense. We collect blood and 24-hour urine samples early every morning and perform analyses that enable us to measure plasma volume, oxidative stress, hematocrit, hemoglobin and specific hormone concentrations. We also perform ultrasonography with each subject multiple times a day to measure cerebral blood flow and vascular resistance, as well as cardiac function. In order to maximise this opportunity we have merged several pertinent research questions, however the main aim of the study is to better determine the mechanisms that govern plasma volume regulation during acclimatisation to high altitude – and furthermore how plasma volume regulation and increased blood viscosity may impact other aspects of human physiology. Recently, we have also been working closely with our two resident climbers (Simone Moro and Tamara Lunger) to optimise their acclimatisation and preparation for their latest winter ascent attempts. Here, we mainly focused on assessing their health status whilst ascending them in a stepwise fashion above 7500m to enable their physiology to progressively adapt. Due to the exceptional physiology of both alpinists we have been able to collect multiple biological samples, plus neurocognitive assessments and MRI images to better characterise intermittent acclimatisation to hypobaric hypoxia – really a privilege and an interesting opportunity to pilot scientific protocols with such an elite duo.

How did your research change with the completion of the terraXcube?

Turner: The terraXcube facility as a whole really delivers a long-awaited test environment, which enables us to carry out complex experimental studies in a very safe and highly controllable environment. Here, in the relative comfort of the terraXcube we are able to ensure that participants are comfortable and scientific research is carried out as precisely as possible with some of the best equipment available. Equally, with continuous medical, technical and lab support onsite we are not only improving the validity of tests done and the quality of analyses, but also the safety of both the participants and personnel. We are used to working in much smaller, less sophisticated, normobaric hypoxic chambers or under much more demanding conditions. Due to the nature of our research, we are normally working in isolation and with limited equipment, somewhere on top of a glacier or mountain! Just the fact that we aren’t testing up above 3500 m in a real-world mountainous environment (i.e. Ortles glacier or Everest Base Camp), makes the terraXcube the more viable, accessible and safe research option. Equally, from a logistical perspective, both bringing in personnel and equipment, as well as assessing and removing an individual from this environment is a lot quicker and easier. In the real world environment, the logistics necessary to facilitate this type of work are hugely costly and the environment dictates the success of the scientific team. Here we are able to manipulate the environment and more specifically the altitude equivalent (0 – 9000 m) to deliver optimal data collection and minimise the risks taken to do so. On a lighter note, the benefits also include easy food delivery, the occasional coffee delivery and a fully functioning, private bathroom – so in fact it could even be considered luxurious!

Understanding the mechanisms that drive adaptation or acclimatisation to high altitude is important, as it is apparent in many different scenarios where people have to suddenly ascend to 3500m or higher.

What advancements in research can be made with terraXcube from your perspective?

Turner: Understanding the mechanisms that drive adaptation or acclimatisation to high altitude is important, as it is apparent in many different scenarios where people have to suddenly ascend to 3500m or higher. The growing accessibility to mountainous environments has driven native residents, tourists and the working population higher and higher. Nowadays non-altitude natives are working at higher elevations (sometimes in excess of 4000m) – building roads, or even working in plantations, mines and satellite array sights, such as the Atacama Desert. There are even high altitude models which relate to pilots, astronauts and even off-world shuttle scenarios. Our mission is to explore the effects of altitude and climate on human health. In particular, to study (patho) physiological changes in healthy subjects and those with pre-existent diseases during exposure to hypobaric hypoxia under different climatic conditions. We also aim to develop and validate preventive measures and therapies for high altitude related pathophysiology (i.e., acute mountain sickness, high altitude pulmonary edema, high altitude cerebral edema and even chronic mountain sickness) and other diseases (e.g., cardiovascular, pulmonary and neurological). The terraXcube allows us to do so right here in Bolzano, alongside growing international collaborations and expertise. For example, my specific research focus is related to better understanding the etiology of high-altitude cerebral edema, which involves exploring cerebral fluid dynamics, and cerebral blood flow autoregulation during high altitude exposures. In order to define which mechanisms are underlying this serious high altitude pathophysiology we must undertake highly controlled research, using sophisticated equipment at sustained high altitudes with the collaboration of local MRI facilities. Just another example as to why the terraXcube is crucial to progress research in this field.

From space to South Tyrol, these studies have a broad spectrum of application…

Turner: Yes, the scope for research in the terraXcube is huge and we hope to make considerable headway in both the field of high altitude physiology and mountain emergency medicine. For example, our team has just carried out another excellent project called HEMS, working with medical professionals and helicopter pilots who work in and around mountain rescue services. The idea was to specifically test whether helicopter emergency medics are at all neurocognitively impaired after immediate ascent to high altitudes, to better understand if there is a high altitude scenario that might require oxygen supplementation to ensure personnel are delivering optimal medical care in these challenging environments. The test protocol employed exposed the participants to either a 3000m or 5000m equivalent, where they completed computer-based cognitive assessments, questionnaires, as well as five minutes of CPR to simulate the physical requirement and assess the impact of physical effort.

What about other hypobaric- enabled, climate chambers, why don´t we hear more about them?

Turner: There are several chamber facilities around the world, but only a handful who do similar work, and even less who are able to simultaneously control the level of hypobaria and climate conditions and are willing to share specific information. We have been lucky to be advised by six excellent hypobaric facilities to date. However, in general military sites are usually closed to collaboration. In this regard the terraXcube is very unusual. It is an “open science” facility: open to collaboration and open to sharing results and data with the public and other groups. This institution is very different from any other around the world. We aim to make this facility a platform for work pertaining to advancements in human physiology and high altitude and emergency medicine; currently we sit at the forefront of what can be done in this field and look forward to fruitful collaborations.

Outside of work are the mountains part of your life?

Turner: Absolutely. Actually, it’s part of the reason I chose to come here and not go back to England, I would often come to northern Italy or just across the border in Switzerland to complete training specific to high altitude mountaineering – the Alpine and Dolomiti environment is really second to none! A lot of the work I was doing when I was in the UK and Ireland included working with elite athletes, including high altitude mountaineers, as well as very enthusiastic groups of amateurs – all people very passionate about the mountain environment and what it can offer. I even joined a group called “Women with Altitude”, a great project which inspires female participation in mountain related activities. I try to support them by giving them lectures for free and taking part in summer camps and winter training activities when I get the chance. Mostly, I enjoy hiking and exploring the Dolomiti – however the next step is to get my skiing up to scratch and head out ski-mountaineering with the rest of the institute!

Related Articles

Tecno-prodotti. Creati nuovi sensori triboelettrici nel laboratorio di sensoristica al NOI Techpark

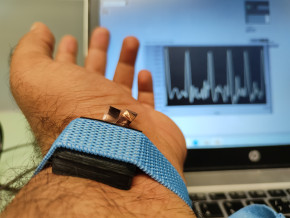

I wearable sono dispositivi ormai imprescindibili nel settore sanitario e sportivo: un mercato in crescita a livello globale che ha bisogno di fonti di energia alternative e sensori affidabili, economici e sostenibili. Il laboratorio Sensing Technologies Lab della Libera Università di Bolzano (unibz) al Parco Tecnologico NOI Techpark ha realizzato un prototipo di dispositivo indossabile autoalimentato che soddisfa tutti questi requisiti. Un progetto nato grazie alla collaborazione con il Center for Sensing Solutions di Eurac Research e l’Advanced Technology Institute dell’Università del Surrey.

unibz forscht an technologischen Lösungen zur Erhaltung des Permafrostes in den Dolomiten

Wie kann brüchig gewordener Boden in den Dolomiten gekühlt und damit gesichert werden? Am Samstag, den 9. September fand in Cortina d'Ampezzo an der Bergstation der Sesselbahn Pian Ra Valles Bus Tofana die Präsentation des Projekts „Rescue Permafrost " statt. Ein Projekt, das in Zusammenarbeit mit Fachleuten für nachhaltiges Design, darunter einem Forschungsteam für Umweltphysik der unibz, entwickelt wurde. Das gemeinsame Ziel: das gefährliche Auftauen des Permafrosts zu verhindern, ein Phänomen, das aufgrund des globalen Klimawandels immer öfter auftritt. Die Freie Universität Bozen hat nun im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts eine erste dynamische Analyse der Auswirkungen einer technologischen Lösung zur Kühlung der Bodentemperatur durchgeführt.

Gesunde Böden dank Partizipation der Bevölkerung: unibz koordiniert Citizen-Science-Projekt ECHO

Die Citizen-Science-Initiative „ECHO - Engaging Citizens in soil science: the road to Healthier Soils" zielt darauf ab, das Wissen und das Bewusstsein der EU-Bürger:innen für die Bodengesundheit über deren aktive Einbeziehung in das Projekt zu verbessern. Mit 16 Teilnehmern aus ganz Europa - 10 führenden Universitäten und Forschungszentren, 4 KMU und 2 Stiftungen - wird ECHO 16.500 Standorte in verschiedenen klimatischen und biogeografischen Regionen bewerten, um seine ehrgeizigen Ziele zu erreichen.

Erstversorgung: Drohnen machen den Unterschied

Die Ergebnisse einer Studie von Eurac Research und der Bergrettung Südtirol liegen vor.