Dreaming of a professional soccer career

As part of our Inside edition, we go behind the doors of Eurac Research, to discover the people who keep the wheels turning at our headquarters. In a revealing interview Kydoe Sarr Ibrahima recounts his escape from The Gambia and the winding road that brought him to Bolzano/Bozen where he is currently working at Eurac Research in the maintenance department.

Kydoe, you’ve been in Europe for eight years, seven in Italy and for four in South Tyrol. What was life in The Gambia like before you left at the age of 20?

Kydoe Sarr Ibrahima: I had a good childhood. My big dream was always to become a professional soccer player. I grew up with my grandmother because my parents emigrated to England when I was two which as a former British colony was easier back then. They always sent money to my grandmother, my three siblings and me. Visits weren’t possible, so I was almost an adult when I saw my mother again for the first time after 15 years.

In July 2014, after ten hours at sea, the overcrowded rubber boat began leaking so badly that we were about to sink. We got rescued by a merchant ship that took us to Agrigento.

You belong to the Serer, an ethnic group which makes up 2.8% of the population. Were you discriminated against because of this?

Kydoe: I was never persecuted for belonging to a minority or for my language or culture. I am a Muslim like over 90% of the population in The Gambia. My reasons for fleeing were quite different - we were living in a dictatorship at the time, there were human rights violations, election fraud and coup attempts. The economy was down, and all the young people wanted to leave. I set my mind on going to Italy and becoming a professional soccer player. I had to lie to my grandma, which I still regret. I told her I was going on a soccer training camp for two to three weeks in neighbouring Senegal.

You came to Italy from Libya on a refugee boat. How did you manage the 3,500 kilometres from The Gambia to Libya?

Kydoe: I was on the road for five months. I had far too little money: for the bus tickets and, at every border, you had to give money to the officials. I had to cross seven borders: Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Algeria and Libya, constantly interrupting my journey to work as a day labourer. Often, we were not paid or only very poorly for cleaning, harvesting or construction work. Our small trucks, overflowing with refugees, were repeatedly held up by gangs. We had to pay them to go on, we were beaten, and many were even abducted. My best friend in The Gambia sent me all his money so I could get to Tripoli.

How did you finally make it from Tripoli to Sicily?

Kydoe: In Tripoli, my money was gone, and I had to work to earn the money for the crossing, the equivalent of 500 euros. Agents run around the port and the markets in Tripoli, telling you when the next boat will leave and how much it will cost. I had the impression that the Libyan police works closely with the smugglers. There were 54 of us, including eight women and six children. This was in July 2014, and after ten hours at sea, the overcrowded rubber boat began to leak so badly that we were about to sink. Fortunately, the sea was calm. We were scared to death and got lucky that a merchant ship brought us to Agrigento.

What happened next?

Kydoe: We ended up in a mixed refugee camp near Agrigento where I was registered, questioned about my reasons for fleeing and fingerprinted. The usual procedure. The Italian authorities treated us with respect, but we had nothing to do. There were no aid organizations, no work, no Italian courses. There was violence among the refugees. We were eight men in one room, separated from the women and children. I was there for two years. Twice a day a car drove from the camp to the city, on foot it was two hours. The daily routine was to be at the work line in Agrigento at 5am. I always stood at the same roundabou with many others and by 7am at the latest, farmers had usually picked us up to help with the grape or olive harvest, we earnt about 20 euros a day.

How did you feel at that time?

Kydoe: At least my family knew I was alive. Of course, naïve as I was, I expected a completely different life in Europe. Two years in Sicily condemned me to do nothing and have no perspective at all. As a political refugee, I couldn’t go back. I took a bus (illegally) to Germany. In Mannheim I immediately reported to the police and applied for asylum on political grounds. Then I came to a refugee home in Kirchheim unter Teck near Stuttgart in Baden-Württemberg. I was there for six months, and life improved: there were volunteers, a library, and German courses.

The beginnings of a new chapter?

Kydoe: I was too old to attend school and had to earn the money for the courses myself. I learned German quickly and soon reached above A 1 level. I was then able to work as a mediator between the municipality and the refugees. We organized parties, cooking evenings and other meetings so that locals and migrants could get to know each other better. For the first time, I felt really good and even found an apartment with four other refugees. But then the situation changed, because of the Dublin Regulation I had to return to the country where I had filed my first asylum application. I took the Flixbus back to Agrigento. Again, no work or support. So, back to Germany by Flixbus. German friends helped me and would have been able to find companies to hire me but with the EU asylum system, no chance - even with a lawyer. My German helpers wanted to place me in the north of Italy, where there was work. First Brescia and then Bolzano/Bozen - because of my German.

How did you get on in South Tyrol?

Kydoe: Luckily it was summer so I could sleep outside for the first month. I immediately contacted Caritas on arrival, but they didn’t have any accommodation. Finally, thanks to Elmira Cola from Binario 1, I was allowed to stay in a refugee home. I started a German course at the university and got a job harvesting apples. Then a Caritas home for another month, but unfortunately, we had to leave there at 8am and stay out till 7pm. We were forced to be on the street all day. Then I was lucky, I met pastor Michael Jäger, who got me a place for five months at the Protestant church. Then my German teacher from the university paid for me to stay in the youth hostel for a week. At the same time, I found a job at a timber company and could finally play soccer.

You then trained with FC Bozen?

Kydoe: Only for a short time. Without contacts and time, it was difficult. I was already too old to be a professional. But, through soccer I met Hannes Huber, who tried helping me find an apartment. It was impossible due to my skin colour. So, Hannes’ aunt took me in for a trial period of two weeks which turned into three years, for which I am infinitely grateful. Soccer is still my passion - I now play for SSV Leifers in the regional league.

My wife would like to join me in Bolzano/Bozen with our two daughters. But starting from scratch in a completely foreign culture to which they will never belong, no matter how hard they will try, makes me anxious.

How did you end up at Eurac Research?

Kydoe: I worked with llamas and alpacas in Renon: riding the llamas, giving tours, and feeding the baby llamas. I met some kids whose parents told me about Eurac Research, and I applied for the job as a janitor. Stephan Ortner hired me right away. I now know almost all the employees and feel fully integrated.

You also have two children yourself.

Kydoe: My two girls are my greatest happiness. Unfortunately, they live with my wife in The Gambia. Officially, I am not allowed to return to my home country, but I have entered the country illegally via Senegal twice in recent years in order to see them and my grandmother, who passed away last year. My wife and daughters need the money I earn here to make ends meet. My wife would like to join me in Europe but in my experience, I’m not sure that’s good for them. My girls go to school in Gambia, have all their friends there. Starting from scratch in Bolzano/Bozen, in a completely foreign culture to which they will never belong, no matter how hard they will try, makes me very thoughtful. On the other hand, my kids need me, and I want nothing more than to be with them.

Credit foto: Eurac Research/Ivo Corrà

Related Articles

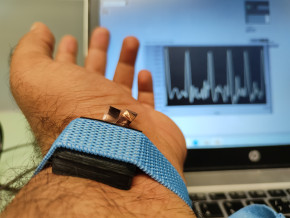

Tecno-prodotti. Creati nuovi sensori triboelettrici nel laboratorio di sensoristica al NOI Techpark

I wearable sono dispositivi ormai imprescindibili nel settore sanitario e sportivo: un mercato in crescita a livello globale che ha bisogno di fonti di energia alternative e sensori affidabili, economici e sostenibili. Il laboratorio Sensing Technologies Lab della Libera Università di Bolzano (unibz) al Parco Tecnologico NOI Techpark ha realizzato un prototipo di dispositivo indossabile autoalimentato che soddisfa tutti questi requisiti. Un progetto nato grazie alla collaborazione con il Center for Sensing Solutions di Eurac Research e l’Advanced Technology Institute dell’Università del Surrey.

unibz forscht an technologischen Lösungen zur Erhaltung des Permafrostes in den Dolomiten

Wie kann brüchig gewordener Boden in den Dolomiten gekühlt und damit gesichert werden? Am Samstag, den 9. September fand in Cortina d'Ampezzo an der Bergstation der Sesselbahn Pian Ra Valles Bus Tofana die Präsentation des Projekts „Rescue Permafrost " statt. Ein Projekt, das in Zusammenarbeit mit Fachleuten für nachhaltiges Design, darunter einem Forschungsteam für Umweltphysik der unibz, entwickelt wurde. Das gemeinsame Ziel: das gefährliche Auftauen des Permafrosts zu verhindern, ein Phänomen, das aufgrund des globalen Klimawandels immer öfter auftritt. Die Freie Universität Bozen hat nun im Rahmen des Forschungsprojekts eine erste dynamische Analyse der Auswirkungen einer technologischen Lösung zur Kühlung der Bodentemperatur durchgeführt.

Gesunde Böden dank Partizipation der Bevölkerung: unibz koordiniert Citizen-Science-Projekt ECHO

Die Citizen-Science-Initiative „ECHO - Engaging Citizens in soil science: the road to Healthier Soils" zielt darauf ab, das Wissen und das Bewusstsein der EU-Bürger:innen für die Bodengesundheit über deren aktive Einbeziehung in das Projekt zu verbessern. Mit 16 Teilnehmern aus ganz Europa - 10 führenden Universitäten und Forschungszentren, 4 KMU und 2 Stiftungen - wird ECHO 16.500 Standorte in verschiedenen klimatischen und biogeografischen Regionen bewerten, um seine ehrgeizigen Ziele zu erreichen.

Erstversorgung: Drohnen machen den Unterschied

Die Ergebnisse einer Studie von Eurac Research und der Bergrettung Südtirol liegen vor.